Essays

What Do We Remember When We Remember War?

MICHAEL J. ALLEN

Associate Professor, Department of History

Northwestern University

Why do we build war memorials, Kyle Henry asks in his short documentary film Half-Life of War, and who do we build them for? Do we build them to remember or to forget? Do we build them to honor the fallen and remember their sacrifice? Or do we build them to comfort the living and to assuage our guilt for causing such sacrifice? Do we build them to reflect on war's realities or to blind ourselves to those realities? If they are meant to prompt reflection why do we so often seem not to notice them? Did the war dead die to go unnoticed?

Uneasy with the quotidian obscurity fated for all war memorials, Henry seeks to focus our attention on these markers and to reinscribe them with war's violence by moving from tranquil but overlooked memorials to forlorn national cemeteries as his film progresses, punctuating close-ups of grave markers with syncopated gun shots before his camera comes to rest on a fresh grave in the film's closing moments. It is one of the 1.5 million graves of dead soldiers that checker the American landscape, along with the 218,000 American war dead buried and memorialized overseas.

With the United States at war almost constantly since 1941 there is no shortage of wars to remember, and no want of war dead to memorialize. Yet, oddly, the more ubiquitous war becomes, the more difficult it is to see clearly, or to see at all. And the more war memorials we build, the less likely we are to notice them. Half-Life of War seeks to refocus our attention on these mementos and to revivify them with political and moral force.

The first American national cemetery was constructed at Gettysburg in October 1863. One month later, President Abraham Lincoln marked the occasion with the Gettysburg Address. Standing in the "Soldiers' National Cemetery" as the recovery and reburial of the dead continued around him, Lincoln called on the memory of "these honored dead" to found "a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal."

Lincoln's words "remade America," as historian Garry Wills has put it. By linking wartime blood sacrifice to national rebirth, Lincoln sacralized the war dead and the nation for which they fought, putting soldier sacrifice at the center of the national story just as Christ's sacrifice lies at the heart of the nation's dominant Christian faith. Both promised eternal life after death, with the war dead living on in the memory of the nation they had died to redeem.

The power of Lincoln's brief Gettysburg oration never diminished. The memorial traditions depicted in the Half-Life of War sprang from that moment, with national cemeteries becoming ubiquitous in the United States and throughout the world after that moment. Until Gettysburg the ordinary soldier dead were typically abandoned to oblivion wherever they fell. Reburial at state expense was reserved for high-born officers and local boys killed close to home, while war memorials featured general officers on horseback, not common soldiers on foot. After the Revolutionary War, for instance, 11,000 Americans who perished aboard British prison ships laid unburied in Brooklyn with, "skulls and feets, arms and legs, sticking out of the crumbling bank in the wildest disorder," as one contemporary put it, until they were finally entombed in 1808, twenty-five years after their deaths. All that changed with the Civil War, which ushered in the national cemetery and the common soldier war memorial, memorial innovations meant to recognize and instill the new democratic nationalism that emerged from that cataclysm.

To this day one can find the wartime sacrifices of the common soldier venerated on the National Mall, where the Gettysburg Address is inscribed in white marble at the Lincoln Memorial, where the names of every American killed in Vietnam are engraved on the black granite of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and where a star at the World War II memorial marks every 100 Americans killed in that conflict. Across the Potomac, 400,000 soldiers and their wives lay buried at Arlington National Cemetery. As Half-Life of War illustrates, since the Civil War memorials to the American war dead have been built in communities and crossroads across the country.

Yet despite or because of their pervasiveness, war memorials largely go unnoticed, especially in our everyday lives. The reasons for this are complicated and don't necessarily prove disinterest on the part of the public. The things we value most are often honored more in the breach than in the observance, and it is undeniable that the selfless sacrifice of the ordinary American soldier remains one of the most sacrosanct ideals in American public life, thus the compulsion to "support the troops" no matter what, even when those troops might best be served by more critical speech and less lip service. The inexorable passage of time also takes its toll. Every war has a memorial half-life that it reaches roughly fifty-years from its end as its veterans age and die before receding from living memory and into history books.

But it does seem to me that there is something more at work than time's passage in our current inattention to war, something more deliberate, something closer to war-weariness and battle fatigue. After fourteen years of uninterrupted war the very longevity and boundlessness of the "war on terror" poses problems for would-be memorialists—what wars are we talking about and where? What should we call them? How to distinguish them? When should we begin and end? Americans are accustomed to thinking of war as a discrete event in a particular time and space, but the war on terror seems to defy any easy boundaries. And who are the victims of these wars and how should they be remembered? Americans no longer die in large numbers in the wars we fight, but growing percentages do suffer life-long trauma, much of it invisible to non-veterans. Is it still appropriate to honor their sacrifice solely by honoring the war dead? Finally, in contrast to much of American history, veterans can no longer be assumed to represent the nation—the All-Volunteer Force is too distinctive for such an equation, coming as it does disproportionately from white micropolitan communities that are politically and sociologically distinct from most of the United States. In many respects the National September 11 Memorial and Museum offers Americans a way to remember the war on terror that is more familiar to them, and far more flattering to their self-image, than anything they could build to the servicemen and servicewomen who fought in the troubled wars that followed.

One senses that discomfort with war's omnipresence in recent decades is somehow related to the disinterest in war memorials that Half-Life of War documents. Whether this means the reverse—that calling our attention to war memorials and the deaths they mark will further discomfit a nation enamored of war—is hard to say. Some might hope that the gunshots that reverberate in Kyle Henry's film might jolt viewers into pained recognition of war's costs, which it puts on vivid display. But I would contend that so long as Americans persist in representing themselves as the sole or primary victims of the wars that they wage and so long as they believe that war preserves rather than threatens democracy, they will continue to wage war too readily and too often, resulting in still more war memorials.

Michael J. Allen is Associate Professor of History at Northwestern University and author of Until the Last Man Comes Home: POWs, MIAs, and the Unending Vietnam War, available from the University of North Carolina Press.

The Sorrowful History of Half-Life of War

TOM PALAIMA

Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics

University of Texas at Austin

In his deeply personal and moving director’s statement, Kyle Henry asks three questions about the memorials strewn across the United States relating to our many wars and our many dead soldiers: Do these monuments accurately reflect the trauma of the experience of war itself? Do we create them to remember or to forget? And why do we then neglect even these sanitized memorials, forgetting they even exist within our midst?

The answers to Henry’s questions are inside each and every one of us. He knows this, and the very title of his film documentary suggests answers. He uses images and sounds connected with our many American wars and with how our war monuments are situated in our everyday lives to get us to look at them and then to question our relationship to them. We owe answers to ourselves and to all those who died fighting our wars.

War memorials and war monuments have a long history in western culture because wars have an equally long history. The very Indo-European roots of the two words indicate that their original purpose was to get us to do what Half-Life of War urges us to do: to keep in mind (*smer-, reduplicated as me-mor-) and to think about (*men-, in so-called o-grade *mon-) all those wars and the fellow human beings who fought and died in them.

General Douglass MacArthur famously misattributed the comment that “only the dead have seen an end to war” to Plato. It was actually a thought that the philosopher George Santayana had at the end of World War I when he observed how naively eager British veterans were to put the war behind them. They desperately wanted to believe that an armistice and a solemnly enacted peace treaty meant a lasting end to the virtually indiscriminate mass slaughter of modern mechanized warfare. Yet the impulse identified by Santayana and MacArthur is a natural collective human response to the pain and suffering caused by war. To forget is a kind of opiate. And so we are left with Kyle Henry’s questions.

Of course, monuments of war cannot and never have captured the trauma of war itself. But that trauma is nonetheless truly radioactive. Every single act of violence experienced in the sphere of war alters the lives of the soldiers involved forever and also affects the lives of everyone who later comes into contact with them.

Yehuda Amichai, an Israeli poet with a lifelong direct experience of war after war after war, gets this terrible point across in his powerful short poem “The Diameter of the Bomb.” Death and wounding cause grief and sorrow that radiates outward, eventually “includ[ing] the entire world.” If we think about it long enough, it even takes away belief in God and in human virtue. So we generally prefer not to think about it.

The ancient Greeks knew this, and so, in a period well before public education existed, they held regular communal ceremonies where oral songs were performed that hymned the realities of war, for soldiers in the field and veterans returned home, for families left behind or families threatened in besieged cities. Like folk and blues songs in traditions gathered up by modern ethnomusicologists, Greek epic and elegiac song poems laid out the hard realities, the irremediable pain, the clear randomness of deaths and wounds—Why him and not him? Why my husband (or son or brother or father) and not theirs?—like so many patients etherized upon tables for the whole community to examine and process.

War memorials serve a similar communalizing purpose. The earliest that we can point to are simple upright stone stelai, like the modern stone grave markers that stand in anonymous massed formation in Henry’s stark, wintry, pathos-laden closing shot. These stelai from the 16th century BCE stand over the royal shaft graves at the site of Mycenae. On them are carved, before writing was used for such purposes, symbolic images of prowess in the use of the military weaponry that is buried with the aristocratic dead below.

In historical times, according to recent theory, the tropaion, a simple stone battlefield marker, was used to note the place where the victorious hoplite force ‘turned’ (see our word trope for a literary ‘turn’ of phrase) the defeated army. This provided, as it were, an officially fixed point for a common narrative about the brutal clash of infantry soldiers whose understanding of the battle in which they took part was limited to trying to push back, kill or maim the armed soldiers immediately in front of them.

Later, officially inscribed public stone monuments listed the names of the citizen soldiers who had died in specific campaigns in a given year. They were listed by the tribes with which their extended families or clan groups were affiliated, often beneath a header giving some brief information about the where and the when of their fighting. These are virtually identical to the granite or marble stelai with engraved or raised letters, sometimes colored in black or white or gilding, that are the focus of much of the last half of Half-Life of War.

The names are critically important. Think of the refrain in Woody Guthrie’s song about the soldiers who died when the first US navy ship, the destroyer Reuben James, was sunk by a German submarine on 31 October 1941: “Tell me what were their names, tell me what were their names, /Did you have a friend on the good Reuben James?” Notice Guthrie’s focus on personal connections. Did you have a friend?

Public communal commemoration is clearly for the living, to give the senseless deaths of loved ones some kind of meaning. For the Greeks of the heyday of ancient Athens, we have no records of victory parades. Since wars were an annual given, a terrible fact of everyday life, they focused on paying tribute to the dead. In a culture wherein even a virtuous life did not bring rewards in an after-life, primary importance was given to perpetuating the names of fallen soldiers on public stone records and in the very names of sons and grandsons. So far as I know, however, there is no indication that their public stone inscriptions suffered less communal disinterest over time than ours.

My conclusion may seem cynical, but it is derived from a long view of human history and human behavior surrounding the collective use of killing force that we call war. Human beings have short attention spans and nearly everything for each of us is personal, unless we try hard to see and feel and remember it otherwise.

Woody Guthrie knew this. His original intention was to sing out in a song the names of all the sailors who accompanied the Reuben James to “the cold ocean floor.” He was told no one would be interested in such a song. That sounds terrible, but it was no doubt true and good advice.

Those who are most moved visiting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial or the Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II in Washington DC or the National September 11 Memorial in New York city are the men, women and children who reach up to touch the carved names of family members or friends. They are disposed to respond personally.

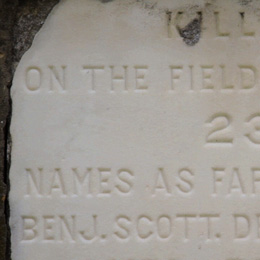

What Half-Life of War can do is to get us to think of each and every name on all our war memorials as somebody’s son, brother, father, uncle or husband—and now daughter, sister, mother, aunt, wife or life partner. We can develop true empathy and sincere reverence for the dead. If that seems too big a task, imagine your own name or your son’s or grandson’s instead of Benjamin Scott’s on the stone where Henry’s camera captures:

KILLED ON THE FIELD OF BATTLE 23.NAMES AS FAR AS KNOWNBENJ. SCOTT. DRUMMER BOY.

Tom Palaima, a MacArthur fellow for his work in Aegean prehistory and early Greek language and culture, is director of the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory in the Department of Classics at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a regular commentary writer for the Austin American-Statesman and contributes to The Texas Observer, Michigan War Studies Review, NPR, and other outlets. Learn More

This film was produced with a grant from the Chicago Digital Media Production Fund, a project of Voqal Fund administered by Chicago Filmmakers.

Half-Life of War

© 2016 | Contact: halflifeofwar@gmail.com